The purpose of this pilot initiative is to assist local communities in Cameroon, and perhaps ultimately throughout the Congo Basin, to protect their forest resources using PES. The initiative seeks to change forest management practices and enable local communities to practice sustainable resource management and receive direct payment for their environmental performance. ‘Performance’ is what distinguishes REDD+ initiatives from other conservation efforts (Blom et al. 2010). Beyond having local impact, the initiative aims to nourish the debates that are influencing the development of national REDD+ policy in Cameroon, even though government support for the initiative has been lukewarm. This chapter describes the two villages (SEC1 and SEC2) that are the focus of this initiative. Households in both villages have expressed willingness to base exploitation of their forests on principles of ecosystem conservation in the hope that in return, they will receive poverty-reducing compensation. This is a pioneering step in Cameroon because all other villages with community forests have set their sights on logging. Thus, this initiative is taking up the challenge of reconciling local development and global challenges, i.e. by reducing emissions that cause global warming and thus harm economically fragile countries. This chapter illuminates this unique approach in Cameroon by describing the initial context of the study villages, the strategy for the initiative, the challenges facing it and lessons learned from its implementation.

11.1 Basic facts: Where, who, why and when

11.1.1 Geography

The two villages targeted by this initiative are located in the south and east regions of Cameroon (Figure 11.1). SEC1 is in the Dja-and-Lobo Division, south region, and is subdivided into three land types: community forests (1043 ha), the agroforestry zone and lands claimed by the community in the Kom Reserve (20,800 ha). SEC2 is in the Haut-Nyong Division, east region. It has a community forest (1759 ha) that covers the whole village (1910 ha), apart from minor claims in the nearby forest management unit.

Figure 11.1 Map of the REDD+ initiative in SE Cameroon.

Data sources: CED Cameroon, GADM and World Ocean Base.

The dominant forest type is a combination of dense, humid, evergreen forest and dense, humid, deciduous forest. In SEC1, some parts of the forest are flooded throughout the year while other parts are well drained. The forest cover is generally dense in the northern part of the community forest, except for a few areas that have been cleared to open up fields and pathways leading to the villages. SEC2 has practically no swamp forests. The community forests are divided into several sections, including relatively undisturbed forest, disturbed forest, regenerating forest, permanently flooded forest and agricultural fields (Plan Vivo 2010).

11.1.2 Stakeholders and funding

The PES initiative is the outcome of a partnership between the Centre pour l’Environnement et le Développement (CED), BioClimate Research & Development (BioClimate) and the Rainforest Foundation UK. The initiative was selected out of seven initiatives to receive funding from the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) and is part of the first round of initiatives to be financed out of the USD 100 million Congo Basin Fund (CBFF). The CBFF was set up by the governments of the UK and Norway in 2007 and is run by the African Development Bank. CED was created in 1994 and has grown to become one of the main defenders of community forests in Cameroon and more broadly throughout the Congo Basin. It is responsible for implementing and coordinating the initiative, which includes payments to communities. BioClimate participated actively in preparing the initiative, in particular by obtaining the DFID grant, and since mid-2010 it has been serving as an external advisor. Since 2009, about 12% of the total budget has been allocated to CED as the initiative facilitator. The Plan Vivo Foundation, a partner in implementing the initiative, receives 6%. The remaining 81.5% is for community projects under the PES initiative. CED monitors the process of payments to households and other activities related to land-use systems (Yemefack et al. 2013). CED works in collaboration with the Association des Femmes et Hommes Amis de Nkolenyeng (AFHAN – Association of Friends, Both Women and Men, of Nkolenyeng) for SEC1 and with the Association pour la Traduction, l’Alphabétisation et le Développement Holistique de l’Etre humain (ASTRADHE – Association for Translations, Literacy Programs and the Holistic Development of the Human Being) for SEC2.

The communities have earned Plan Vivo certification for carbon. The January 2010 Plan Vivo PDD (Plan Vivo 2010) indicates that the expected benefits in terms of carbon credits are 15,861 tC for SEC1 and 6884 tC for SEC2 for the 2012–2015 period, and 5418 tC for SEC1 and 53,119 tC for SEC2 for the 2016–2020 period, for a total of 81,282 tC over the 10-year period from 2010 to 2020. These carbon credits can be sold on the voluntary carbon credit market. CED, unlike BioClimate, is not yet convinced of the viability of selling carbon credits, because the global carbon market is characterized by risk and instability, which means that improved living conditions for the local populations cannot be guaranteed. Some people believe that the initiative cannot be implemented until the carbon funds are obtained to build up the initial funding and thus contribute to improving the living conditions of the participating populations (Awono et al. 2014).

11.1.3 Motivation

In Cameroon, as in other tropical countries, agriculture is viewed as the main cause of deforestation (Ndoye and Kaimowitz 2000). This is also true for the sites hosting the PES initiative. In SEC1, activities such as mixed farming (groundnuts, maize, banana, cassava, etc.), new cocoa plantations, the traditional timber trade and the felling of palm trees to make palm wine, cause the most deforestation and forest degradation. Villagers pointed to illegal logging by the elite as an external source of pressure on forest cover (Plan Vivo 2010). The greatest cause of deforestation in SEC2 is from external sources, especially the Bantu (an ethnic group) from other villages who clear forest lands for crop production, especially maize, cassava and groundnuts. Members of the community who gather honey sometimes cut down trees to make their work easier. They also cause bush fires by using fire to reduce bee attacks, leading to deforestation and forest degradation. Despite acceptance of the PES initiative by local stakeholders, some community members and external elites have encouraged the Baka (a second ethnic group) to fell trees for timber. All households in both villages collect fuelwood, which is a non-negligible cause of forest degradation. In Cameroon, as elsewhere throughout Central Africa, the collection of fuelwood and making of charcoal are often connected to swidden agriculture (Schure et al. 2013).

CED, a fervent defender of community forests in Cameroon, has been involved in improving living conditions and reducing deforestation since its creation in 1994 when forest management in Cameroon experienced a crisis. CED has been in contact with the two villages SEC1 and SEC2 since 1999, and helped with capacity building when community forestry was introduced. Conservation projects carried out by the villages and CED began in 2008. These projects resulted from the identification of threats to local forests such as swidden agriculture and small-scale logging (legal and illegal). These threats must be viewed in the context of community forestry, which has forest exploitation as one of its initial objectives. Income from the annual allowable cut, determined through a simple management plan, is dedicated to the needs of the community. But this contributed to the failure of conservation activities in SEC2, where pressures on forests were not just from internal forces, but also from forces and people external to the initiative area. In SEC1, pressures were mainly related to the community’s farming activities, while in SEC2, pressures came mainly from logging companies and hunting. By 2017, there will be a paved road close to SEC1, extending from the town of Sangmelima to the Republic of Congo, which could make the surrounding forestland more vulnerable.

11.1.4 Timeline

The SE Cameroon initiative follows other conservation efforts in the same location, which started around 1995. The initiative was launched in 2008 and made its first conditional payments to the villages in 2012. CIFOR-GCS field studies began in 2010 and the second phase of field research concluded in late 2013 (Figure 11.2).

Figure 11.2 Timeline of the REDD+ initiative in SE Cameroon.

11.2 Strategy for the initiative

The PES initiative is designed to improve forest protection by reducing pressure exerted by the local and migrant populations, and to create alternatives for the communities whose livelihoods depend on the forest. Financial incentives, which stem from the benefits derived from forest protection measures, including carbon storage, have been introduced to support this strategy (Table 11.1). Thus, environmental protection and increased standard of living are viewed from the vantage point of carbon credits. To achieve its goals, the initiative adopted Plan Vivo, a form of certification that can be used to generate carbon credits. The Plan Vivo standards are consistent with UNFCCC REDD+ guidelines and ensure the link with the REDD+ process. To help the communities understand the political framework governing the initiative, CED has held discussions with the communities and distributed posters explaining the REDD+ concept.

The first implementation stage involved obtaining FPIC from the local communities. The next activity, conducted through a participatory approach, entailed demarcating the forestland to be protected and defining an REL to assess the quantity of carbon that would be released into the atmosphere if the initiative was not carried out. CED, together with the local communities, discussed a series of activities (Table 11.1) to lay the groundwork for REDD+ and to generate revenue. A bank account was opened for the community to receive funds generated as a result of the land management protocol. The protocol aims to define different responsibility and payment scenarios to ensure transparency and equity. The commitments of each party are stipulated in a contract between CED and the communities. Performance indicators, supported by predefined criteria such as the total land area to be cleared for agriculture, are used to evaluate the level of community compliance with their commitments to protect certain forest areas. This in turn triggers an annual payments process, with payments being made totally, partly or not at all, depending on the results. The performance assessment has factored in the communities’ priority to protect zones where the forest cover is very dense (the primary forest) and relegating most of their other activities to the so-called secondary forest zones and agricultural zones (fallows). To maintain high productivity on the fallows and secondary forestland, which usually are less fertile than the primary forestland, the initiative provides training in agroforestry techniques that are expected to eliminate the aforementioned threats to forest cover. The pilot initiative has a pre-defined sum set aside for these payments, but if performance does not warrant payment, the money is not lost but is carried over to the next year. The logic underlying the pilot initiative draws on the ideas of apprenticeship and on documenting situations as they occur.

Table 11.1 Activities organized by the communities.

|

Strategy |

Name and description |

Year begun |

|

Restrictions on forest access and/or conversion |

Restrict access of villagers to forest and wildlife |

2009 |

|

Environmental education |

Education program on forest protection |

|

|

Tenure clarification |

Land management plan and mapping |

2010 |

|

Forest enhancement |

Reduced impact of logging |

2011 |

|

Setting up nurseries |

||

|

Forest monitoring committee |

||

|

Livelihood enhancement |

Civic projects (electricity, water, etc.) |

|

|

PES |

||

|

Optimizing NTFPs |

||

|

Training in beekeeping |

||

|

Improvements in farming techniques |

The 81.5% of the budget allocated to the local communities is for community-based sharing rather than individual payments. The forest management committees for the two villages receive the funds on behalf of the communities as stated in the agreement with the proponent. For SEC1, payments will be made to AFHAN and for SEC2 payments will be made to Bouma Bo Kpode (a legal entity that acts as a forest management committee). The 81.5% will be divided in SEC1 into 40% for a village electrification project and 41.5% for micro projects in areas such as beekeeping and NTFPs. In SEC2, 40% will be used for a water supply project and 41.5% for group initiatives such as improved agricultural practices. Participatory mapping and GPS data were used to estimate probable forest cover changes if the initiative were not implemented. The deforestation rate, calculated using a future deforestation prediction model constructed with the assistance of ECOMETRICA and BioClimate, will be used in planning the initiative and looking for a buyer. The models have to be updated every 10 years. CED will monitor forest cover changes through carbon estimation and biomass quantification. Specially trained community members have participated in the demarcation of several plots for the biomass inventory. To monitor forest cover, members of the community have organized a monthly patrolling routine.

11.3 Smallholders in the initiative

SEC1 was founded in 1914 and SEC2 in 1972. The SEC1 community is composed mainly of Bantu of the Fang ethnic group and a small number of Baka. SEC2 is made up of Baka, with some mixed Baka-Bantu households. Those mixed households are generally involved in trade and agriculture (mainly in plantain, cassava and maize). In general, there is little population movement into or out of these villages, except for seasonal migration to SEC1 to meet the needs of cocoa production. Workers come to the village from other regions of Cameroon where land is less fertile, such as the northwest, to offer their services to landowners who typically own at least 2 ha of land.

The economic profiles of the two villages are different. SEC1 is composed mainly of farmers (except for the Baka, a minority group). SEC2 is more oriented toward hunting and gathering, although it also has some agricultural income. In SEC1, cocoa is the main source of income for the Bantu; other sources are livestock, palm wine, plantain, groundnuts, cassava, wickerwork, rattan, maize, cocoyam and bushmeat. Agriculture is the economic mainstay, as it is at the national level (Ndoye and Kaimowitz 2000; Nkamleu et al. 2003). The main source of income for the Baka is through providing labor in fields belonging to the Bantu. They are sometimes paid in kind, e.g. with cassava or other tubers. The Baka also earn a living from hunting, honey gathering and collecting other NTFPs. Like their counterparts in SEC1, the main source of livelihood for the Baka in SEC2 is farming and working in fields owned by the Bantu. Other sources of income include NTFPs such as wild mangos, honey, rattan, palm wine and moabi oil.

The CIFOR-GCS survey included 120 households, 60 in each of the two villages. The households were selected at random after a census of all households in the villages. The sample was further stratified by ethnic group in SEC1 to ensure adequate representation of each of the two groups in the village, which has a majority of Bantu and a minority of Baka. This was not the case in SEC2, which consists mainly of one ethnic group (Baka).

The remainder of this section focuses on village structure, organization and livelihoods using key socioeconomic descriptors. The proportion of all households in the village sampled by CIFOR-GCS was 74% in SEC1 and 38.5% in SEC2. In both villages the village chief leads the community and selects other village notables (with the exception of those with hereditary positions), with the assistance of a council of notables composed mainly of native residents. SEC1 has 4 women out of 17 members on the council of notables, while SEC2 has 2 women out of 10 members. Both villages generate agricultural income, though more so in SEC1 than in SEC2. For some households there has been a downturn in agricultural yields because of lack of seed, vagaries of climate and the limited area of cropland. Thus, CED decided to support community efforts to improve their agricultural production. The nearest markets are far away from both villages. Both villages have had prior contact with a conservation NGO (Table 11.2).

Table 11.2 Characteristics of the two villages studied based on the 2010 survey.

|

SEC1 |

SEC2 |

|

|

Basic characteristics |

||

|

Year founded |

1914 |

1972 |

|

Total number of households |

81 |

156 |

|

Total land area (ha) |

20,800 |

1,910 |

|

Total forest area (ha) |

12,582 |

1,815 |

|

Access to infrastructure |

||

|

Elementary school |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Secondary school |

No |

No |

|

Health center |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Road access in all seasons |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Bank or other source of formal credit |

No |

No |

|

Distance to closest market (km) |

44 |

25 |

|

First experience with a conservation NGO |

2008 |

1995–96 |

|

Agriculture |

||

|

Main agricultural commodity |

Plantain |

Cassava |

|

Crop with highest added value |

African plum |

Cassava |

Table 11.3 shows that SEC1 has better infrastructure and socioeconomic development than SEC2. The average annual household income is USD 4254 in SEC1 compared to USD 2816 in SEC2. The difference stems from higher agricultural production in SEC1, associated with greater average land area controlled by the households (19.9 ha in SEC1 and 4.9 ha in SEC2), and higher investment in livestock production. The SEC1 community has invested six times more than SEC2 in transportation, which probably makes it easier to reach the market to sell their produce. In SEC2, a road to the town of Lomié was improved to serve the needs of the mining industry in the region, an industry whose growth has provided marketing opportunities for the community of SEC2. But since SEC2 has low agricultural output, the village households spend less than villagers in SEC1 on transport.

Table 11.3 Socioeconomic characteristics of households interviewed in 2010.

|

SEC1 |

SEC2 |

|

|

Number of households sampled |

60 |

60 |

|

Household average (SD) |

||

|

Number of adults |

2.5 (1.4) |

2.4 (0.6) |

|

Number of members |

5.9 (3.5) |

4.8 (2.3) |

|

Days of illness per adult |

58.2 (99.1) |

24.0 (30.1) |

|

Years of education (adults ≥ 16 years old) |

5.9 (3.0) |

3.3 (2.0) |

|

Total income (USD)a |

4,254 (3,695) |

2,816 (3,953) |

|

Total value of livestock (USD)b |

71 (152) |

29 (99) |

|

Total land controlled (ha)c |

19.9 (15.4) |

4.9 (4.1) |

|

Total value of transportation assets (USD) |

819 (542) |

168 (127) |

|

Percentage of households with: |

||

|

Mobile or fixed phone |

22 |

0 |

|

Electricity |

17 |

0 |

|

Piped water supply |

0 |

0 |

|

Private latrine or toilet |

10 |

5 |

|

Perceived sufficient income |

42 |

23 |

a Total annual income (12 months prior to survey) from agriculture, livestock, business, wage labor and other sources (remittances, subsidies, pensions), net of costs, in USD; currency converted using yearly average provided by the World Bank.

b Total livestock value at the time of interview.

c Total area of agricultural, forest, other natural habitat and residential areas controlled by the household, either used or rented out.

Close to half (42%) of the SEC1 households said that their income was enough to cover their daily needs (health care, education, food, clothes, etc.), while only 2% of villagers in SEC2 reported that their income covered their needs. In SEC1 on average, the residents had two years more education than those of SEC2 (Table 11.3). At the time of the survey, 17% of the households in SEC1 had electricity (from individual generators) and 22% had a telephone, whereas in SEC2 no households had either electricity or telephones. Neither village had an improved water supply or sanitation system, with only 10% or fewer households having private toilets or latrines and none having piped drinking water (Table 11.3).

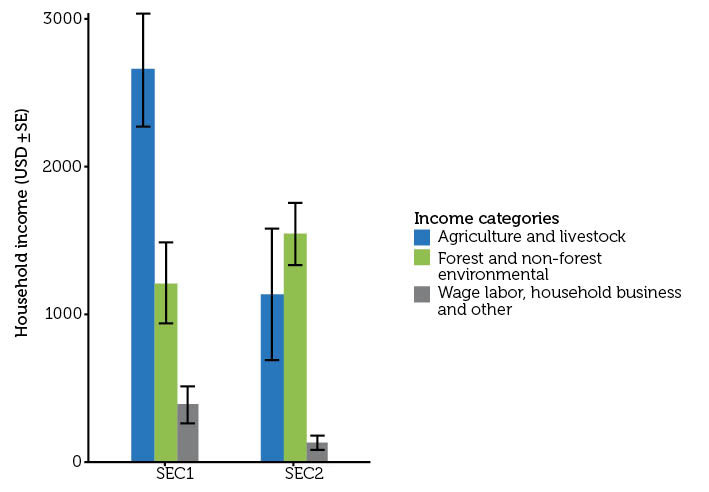

The data presented in Figure 11.3 show the contrasting cultural identities of the two communities. SEC1 focuses on agriculture and livestock production, with an average income per household exceeding USD 2500, while SEC2 focuses on forest and environmental activities, with a much lower average annual household income. However, the distinction between the two villages is becoming less pronounced as the Baka become more interested in agriculture.

Figure 11.4 shows that agriculture alone represents 53% of the two villages’ income, followed by forest and environmental income (39%). The remaining 7% includes livestock, business, wage labor and other income.

Figure 11.3 Sources of income for average household by village (+/- SE) (n = 120).

Figure 11.4 Sources of income for all households in sample (n = 120).

Table 11.4 presents information on the degree of household dependence on forestland and resources in the two study villages. Forest-based activities are a primary or secondary occupation in 15% of households in SEC1 and in 44% of households in SEC2. In both villages, most households get some cash income from forest products, and all households rely on fuelwood for cooking. In both villages, there was a downward trend in both the consumption and sale of forest products in the two years prior to the 2010 interview. Virtually all households in both villages reported clearing forestland for agriculture in the two years prior to the interview, and most experienced increasing constraints on opportunities to clear forestland.

Table 11.4 Indicators of household forest dependence based on the 2010 survey.

|

SEC1 |

SEC2 |

|

|

Number of households sampled |

60 |

60 |

|

Household average (SD) |

||

|

Share of income from forest |

21.03 (23.58) |

63.30 (23.78) |

|

Share of income from agriculture |

64.87 (26.46) |

26.79 (21.09) |

|

Area of natural forest cleared (ha)a |

2.06 (1.87) |

2.15 (1.47) |

|

Area of secondary forest cleared (ha)a |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.02 (0.13) |

|

Area left fallow (ha)b |

2.02 (1.39) |

1.71 (0.99) |

|

Distance to forests (minutes walking) |

75 |

120 |

|

Percentage of households |

||

|

With agriculture as a primary or secondary occupation (adults ≥ 16 years old)c |

94 |

96 |

|

With a forest-based primary or secondary occupation (adults ≥ 16 years old)d |

15 |

44 |

|

Reporting increased consumption of forest productse |

7 |

2 |

|

Reporting decreased consumption of forest productse |

64 |

80 |

|

Obtaining cash income from forest productsf |

78 |

100 |

|

Reporting an increase in cash income from forestf |

11 |

24 |

|

Reporting a decrease in cash income from forestf |

55 |

58 |

|

Reporting fuelwood or charcoal as primary cooking source |

100 |

100 |

|

Leaving land fallowg |

88 |

95 |

|

Clearing forestg |

95 |

98 |

|

Reporting decreased opportunity for clearing forestg |

88 |

93 |

|

Clearing land for cropsg |

95 |

98 |

|

Clearing land for pastureg |

0 |

0 |

a Average no. of hectares cleared over the past two years among households that reported clearing of any forest.

b Average no. of hectares left fallow among households that reported leaving any land fallow.

c Percentage of households with at least one adult reporting cropping as a primary or secondary livelihood.

d Percentage of households with at least one adult reporting forestry as a primary or secondary livelihood.

e Percentage of households among those that reported any consumption of forest products over the past two years.

f Percentage of households among those that reported any cash income from forest products over the past two years.

g In the two years prior to the survey.

11.4 Challenges facing the initiative

The introduction of sustainable landscape management at the community level creates as many challenges as there are categories of actors who covet forest resources. In the beginning, forest communities were exploited without considering sustainable development. In particular, they were exploited by logging companies that encroached on their lands and threatened their territory. The Government of Cameroon adopted a law authorizing communities to create their own community forests by demarcating boundaries and drawing up a management plan that could contribute to community development by generating economic benefits. The CED initiative seeks to develop the potential for community forests through financial incentives linked to the mitigation of climate change (Somorin 2010). The ultimate aim of the initiative is to integrate global issues into the conduct of daily subsistence activities in such a way that villagers are more responsive to them. The initiative takes a participatory approach to adapting sustainable forest management to meet the needs of communities. The innovative character of the initiative however, has created some doubts about, for instance, the reliability of the NGO’s commitment to the community, the real effects of the initiative, and the payments.

Baka Hut. (Patrice Levang/CIFOR)

Although local leaders insist they have adopted the main principles of sustainable management, there are a few dissident voices in each village. Issues of concern include benefit sharing and equity (Awono et al. 2014), and potential restrictions on land access. There are questions about whether the new techniques promoted by the initiative will guarantee better agricultural yields. Will income levels decrease, and if so, will adequate compensation be provided? Will their efforts really contribute to protection of forests and lessen the threats posed by climate change? Will conflicts arise that could seriously threaten the rights of the local communities to their lands and resources? (Awono et al. 2014). The laws that define the status of the community forests recognized managerial rights for a period of 25 years. This includes the right of the community to sell products harvested from its forestland, but it does not confer ownership rights to those lands. Participatory mapping has cleared up the problem of boundaries and land use on the basis of forest categories and land used by the community, but the PES initiative does not include all the land being claimed by these communities, and does not include all households, thus causing an imbalance in the involvement of community members. Furthermore, in both villages, especially in SEC2, people from the neighboring villages are moving in to exploit forest resources and sometimes to farm.

The proponents, who see the initiative as a point of reference for structuring REDD+ policy at the national and the subregional level, question the capacity of the local government to introduce reforms that could guarantee tenure security for the local populations and recognize their carbon rights (Awono et al. 2014). There is also some doubt about the potential for increased revenues earned from new cropping practices to encourage the expansion of agriculture and, hence, degradation of forest cover. There is also potential for other types of leakages and for increased pressure on forest resources by villages not involved in the initiative.

Despite these challenges, the two villages have decided to bank on this initiative as a tool to make their local economies more dynamic through income diversification (beekeeping, livestock production) and the application of modern cropping techniques designed to improve yields and standards of living. If these incentives are sufficiently convincing and adapted to pave the way for the emergence of a new type of forest management, this could trigger positive, coordinated change at the grassroots level.

11.5 Lessons from the initiative

CED launched an important innovation by starting a PES initiative in community forests that were formerly limited to timber production. The acceptance of the initiative by local communities suggests that this model of forest management, based on funds for environmental performance, might be viable in other areas of Cameroon. Local acceptance was facilitated by the proponent’s participatory approach from the very beginning of the process. Although the expected results are not guaranteed, the initiative is already seen at the national level as an analytical laboratory for identifying the best ways to involve local communities in efforts to make the reduction of emissions from deforestation and forest degradation part of the solution to the thorny problem of climate change. The experience of this initiative makes it clear that interventions to mitigate climate change will only be well received at the local level if the rights of the community are made clear and standards of living are improved. Capacity building at the grassroots level increases the chance that opinions expressed at that level will be respected and consequently, the benefits of new REDD+ mechanisms will be more equitably shared. Thus, there is a great need for communities to organize themselves and coordinate their efforts in order to both defend their interests and manage their forest resources sustainably.

11.6 Acknowledgments

We would like to heartily thank all the inhabitants of SEC1 and SEC2 for their positive and welcoming attitude and their willingness to participate. We are deeply grateful to CED for agreeing to work with CIFOR-GCS. We are indebted to Annie Flore Djouguep, Jean Paul Eyebe and Célestine Yvette Ebene Onana, who collected the data for this chapter with eagerness and dedication.